Object Calisthenics

Object Calisthenics has been introduced the first time by Jeff Bay. Object Calisthenics outlines 9 basic rules to apply when writing code.

Object Calisthenics are programming exercises, formalized as a set of 9 rules invented by Jeff Bay in his book The ThoughtWorks Anthology. The word Object is related to Object Oriented Programming. The word Calisthenics is derived from greek, and means exercises under the context of gymnastics. By trying to follow these rules as much as possible, you will naturally change how you write code. It doesn’t mean you have to follow all these rules, all the time. Find your balance with these rules, use some of them only if you feel comfortable with them.

The idea of Object Calisthenics is that the high-level concepts and principles of good object-oriented programming can be distilled into low-level rules to follow.

These rules focus on maintainability, readability, testability, and comprehensibility of your code. If you already write code that is maintainable, readable, testable, and comprehensible, then these rules will help you write code that is more maintainable, more readable, more testable, and more comprehensible.

Why

Following the rules given here with discipline will force you to come up with the harder answers that lead to a much richer understanding of object oriented programming. If you write a thousand lines that follow all these rules you will find that you have created something completely different than you expected. Follow the rules, and see where you end up. If it isn’t comfortable, back off and see what you can leverage that is comfortable. You might find that if you keep working at it, you’ll find your code naturally conforming to these rules. Most new things worth doing are difficult, allow yourself the chance to internalize them.

7 of these 9 rules are simply ways to visualize and implement the holy grail of object oriented programming – encapsulation of data. In addition, another drives the appropriate use of polymorphism (not using else and minimizing all conditional logic), and another is a naming strategy that encourages concise and straightforward naming standards – without inconsistently applied and hard to pronounce abbreviations. The entire thrust is to craft code that has no duplication in code or idea; code which concisely expresses simple and elegant abstractions for the incidental complexity we deal with all day long.

We should also point out that the more you practice applying the rules, the more the advantages come to fruition. Your first attempts to decompose problems in the style presented here will feel awkward and likely lead to little gain you can perceive. There is a skill to the application of the rules – this is the art of the programmer raised to another level.

1. Only one level of indentation per method

This rule is simple, and applied, greatly reduces complexity.

Just try to keep your method as simple and understandable as you can.

The primary motivation of this rule is that one is not dealing with multiple levels — both indentation and abstraction — at once.

class InsertionSort {

public function sort(array $array) {

// 1 level

for ($i = 0; $i < count($array); $i++) {

// 2 level

$x = $array[$i];

for ($j = $i - 1; $j >= 0; $j--) {

// 3 level

if ($array[$j] > $x) {

$array[$j + 1] = $array[$j];

$array[$j] = $x;

}

}

}

return $array;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

That’s a common example when you can easily spot multiple indentation levels into a method. That’s bad. Bottom line.

You can fix this most of the time, using the Extract Method pattern or in others, composing your objects in order to don’t aggregate all logic in one method. This is also somehow related with Single Responsibility Principle and High Cohesion which are valid as well for methods. If your method has multiple indentation levels, then maybe is not doing only one thing

class InsertionSort {

public function sort(array $array) {

for ($i = 0; $i < count($array); $i++) {

$array = $this->insert($array, $i);

}

return $array;

}

protected function insert(array $array, $i) {

$x = $array[$i];

for ($j = $i - 1; $j >= 0; $j--) {

$array = $this->swap($array, $x, $j);

}

return $array;

}

protected function swap(array $array, $x, $j) {

if ($array[$j] > $x) {

$array[$j + 1] = $array[$j];

$array[$j] = $x;

}

return $array;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

The bottom line: it works. I’ve written much more straightforward code this way, and the result is small methods that can then be pushed out of the current class to the primary object being acted upon, which generally, is the first parameter of the method.

Ever stare at a big old method wondering where to start? A giant method lacks cohesiveness. One guideline is to limit method length to 5 lines, but that kind of transition can be daunting if your code is littered with 500-line monsters. Instead, try to ensure that each method does exactly one thing – one control structure, or one block of statements, per method. If you’ve got nested control structures in a method, you’re working at multiple levels of abstraction, and that means you’re doing more than one thing.

As you work with methods that do exactly one thing, expressed within classes doing exactly one thing, your code begins to change. As each unit in your application becomes smaller, your level of re-use will start to rise exponentially. It can be difficult to spot opportunities for reuse within a method that has five responsibilities and is implemented in 100 lines. A three-line method that manages the state of a single object in a given context is usable in many different contexts.

Use the Extract Method feature of your IDE to pull out behaviors until your methods only have one level of indentation, like this:

class Board {

...

String board() {

StringBuffer buf = new StringBuffer();

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 10; j++)

buf.append(data[i][j]);

buf.append(“\n”);

}

return buf.toString();

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

class Board {

...

String board() {

StringBuffer buf = new StringBuffer();

collectRows(buf);

return buf.toString();

}

void collectRows(StringBuffer buf) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

collectRow(buf, i);

}

void collectRow(StringBuffer buf, int row) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

Buf.append(data[row][i]);

buf.append(“\n”);

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Notice that another effect has occurred with this refactoring. Each individual method has become virtually trivial to match its implementation to its name. Determining the existence of bugs in these much smaller snippets is frequently much easier.

Here at the end of the first rule, we should also point out that the more you practice applying the rules, the more the advantages come to fruition. Your first attempts to decompose problems in the style presented here will feel awkward and likely lead to little gain you can perceive. There is a skill to the application of the rules – this is the art of the programmer raised to another level.

2. Don’t use the “else” keyword

The argument is to reduce the number of branches, keeping long conditional blocks out of the code.

Every programmer understands the if/else construct. It’s built into nearly every programming language, and simple conditional logic is easy for anyone to understand. Nearly every programmer has seen a nasty nested conditional that’s impossible to follow, or a case statement that goes on for pages. Even worse, it is all too easy to simply add another branch to an existing conditional rather than factoring to a better solution. Conditionals are also a frequent source of duplication. Status flags and state of residence are two examples which frequently lead to this kind of trouble:

if (status == DONE)

{

doSomething();

}

else

{

...

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

a) Early Return: If your validating data, than to avoid else you can use early return. E.g You have a java method which takes list as an argument and returns last index of list. ❌ Wrong way:

private Integer getFinalIndexOfList(List<String> names)

{

if (CollectionUtils.isEmpty(names))

{

return null;

}

else

{

return names.size() - 1;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

👍 Right way:

private Integer getFinalIndexOfList(List<String> names)

{

if (CollectionUtils.isEmpty(names))

{

return null;

}

return names.size() - 1;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

b) Polymorphism:

Object-oriented languages give us a powerful tool, polymorphism, for handling conditional cases, but on the other hand we should not hate if/else or conditionals more than we should. Introducing polymorphism too soon will complicate your code.

Lets take a quick example:

We have a class that processes order, and discount is deducted from total amount of item based on the type of customer.

Solution with conditionals:

Customer.java

public class Customer

{

public String type;

}

2

3

4

ProcessOrder.java

public class ProcessOrder

{

public int getOrderGrandTotal(Customer customer, int subTotal)

{

if (customer.type.equals("EMPLOYEE"))

{

return subTotal - 20;

}

else if (customer.type.equals("NON_EMPLOYEE"))

{

return subTotal - 10;

}

return subsTotal;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Solution with polymorphism: Customer.java

public abstract class Customer

{

public abstract int getDiscount();

}

2

3

4

Employee.java

public class Employee extends Customer

{

@Override

public int getDiscount()

{

return 20;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

NonEmployee.java

public class NonEmployee extends Customer

{

@Override

public int getDiscount()

{

return 10;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ProcessOrder.java

public class ProcessOrder

{

public int getOrderGrandTotal(Customer customer, int itemAmount)

{

return itemAmount - customer.getDiscount();

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

Null Object or Optional or Empty list: Dramatically reduces the need for null checking. Lets take an example of lists, we have a invoice class has list of line items, whenever null list is passed to invoice constructor, set it to empty list to avoid null check wherever invoice class is used.

public class Invoice

{

private final String id;

private final List<LineItem> lineItems;

public Invoice(String id, List<LineItem> linesItems)

{

this.id = id;

this.lineItems = lineItems == null ? new ArrayList() : lineItems;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

3. Wrap All Primitives And Strings

Following this rule is pretty easy, you simply have to encapsulate all the primitives within objects, in order to avoid the Primitive Obsession anti-pattern.

If the variable of your primitive type has a behaviors, you MUST encapsulate it. And this is especially true for Domain Driven Design. DDD describes Value Objects like Money, or Hour for instance.

In the Java language, int is a primitive, not a real object, so it obeys different rules than objects. It is used with a syntax that isn’t object-oriented. More importantly, an int on its own is just a scalar, so it has no meaning. When a method takes an int as a parameter, the method name needs to do all of the work of expressing the intent. If the same method takes an Hour as a parameter, it’s much easier to see what’s going on. Small objects like this can make programs more maintainable, since it isn’t possible to pass a Year to a method that takes an Hour parameter. With a primitive variable the compiler can’t help you write semantically correct programs. With an object, even a small one, you are giving both the compiler and the programmer additional info about what the value is and why it is being used.

Small objects like Hour or Money also give us an obvious place to put behavior that would otherwise have been littered around other classes. This becomes especially true when you apply Rule 9, and only the small object can access the value. Note that this does not mean using object wrappers that are available in languages like Java. Using an Integer instead of an int confers no additional advantages in terms of expressing intent, whereas using a wrapper that expresses meaning within the problem domain both clarifies its usage and makes intent evident.

Example:

You have a SMS subscription which has a quantity and is valid for a month and year, you have to store month a as integer. 1 will represent January and 12 will represent December, quantity of SMS can be minimum 1 and maximum 250 and year cannot be less than 1970.

One way of doing it is:

public class SMSSubscription

{

private String id;

private int quantity;

private int month;

private int year;

public SMSSubscription(String id, int quantity, int month, int year)

{

this.id = id;

if (quantity < 1 || quantity > 250)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Quantity cannot be less than 1 or greater then 250");

}

this.quantity = quantity;

if (month < 1 || month > 12)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Month cannot be less than 1 or greater then 12");

}

this.month = month;

if (year < 1970)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Year cannot be less than 1970");

}

this.year = year;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

You can clearly see in above code that SMSSubsctiption is doing more then what it is supposed to do. Quantity, month and year has their own specific behaviors, which must be encapsulated.

Lets do it in a right way, first we will encapsulate quantity, month and year. Quantity.java

public class Quantity

{

private int quantity;

public Quantity(int quantity)

{

if (quantity < 1 || quantity > 250)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Quantity cannot be less than 1 or greater then 250");

}

this.quantity = quantity;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Month.java

public class Month

{

private int month;

public Month(int month)

{

if (month < 1 || month > 12)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Month cannot be less than 1 or greater then 12");

}

this.month = month;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Year.java

public class Year

{

private int year;

public Year(int year)

{

if (year < 1970)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Year cannot be less than 1970");

}

this.year = year;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

and now this this is how SMSSubscription looks like: SMSSubscription.java

public class SMSSubscription

{

private String id;

private Quantity quantity;

private Month month;

private Year year;

public SMSSubscription(String id, Quantity quantity, Month month, Year year)

{

this.id = id;

this.quantity = quantity;

this.month = month;

this.year = year;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

See also:

4. First Class Collections

Any class that contains a collection should contain no other member variables. If you have a set of elements and want to manipulate them, create a class that is dedicated for this set.

Each collection gets wrapped in its own class, so now behaviors related to the collection have a home (e.g. filter methods, applying a rule to each element).

From the original: "any class that contains a collection should contain no other member variables." Said differently, that means that a collection should be wrapped in a class specific to how the collection is used.

Thus the logic for using a collection goes into the wrapper class, instead of in the "client" code. This feels more like working with an object instead of in it.

Behaviors related to the collection have a home

5. One Dot Per Line

Sometimes it’s hard to know which object should take responsibility for an activity. If you start looking for lines of code with multiple dots, you’ll start to find many misplaced responsibilities. If you’ve got more than one dot on any given line of code, the activity is happening in the wrong place. Maybe your object is dealing with two other objects at once. If this is the case, your object is a middleman; it knows too much about too many people. Consider moving the activity into one of the other objects.

If all those dots are connected, your object is digging deeply into another object. These multiple dots indicate that you’re violating encapsulation. Try asking that object to do something for you, rather than poking around its insides. A major part of encapsulation is not reaching across class boundaries into types that you shouldn’t know about.

The Law of Demeter ("Only talk to your friends") is a good place to start.

a.getFoo().getBar().getBaaz().doSomething(); // bad

Note that this rule doesn’t forbid the following:

a.foo(b.foo()); // okay

Rather, it’s a simplified way of stating the Law of Demeter.

It’s worth noting that there are specific places where multiple dots make sense, but these are usually within the context of building a DSL or a design pattern, such as a Builder:

builder.property1("value").property2("value").build();

In this case it doesn’t violate the spirit of the rule since it doesn’t return any internal state or other classes.

6. Don’t Abbreviate

The right question is Why Do You Want To Abbreviate?

You may answer that it is because you write the same name over and over again? And I would answer that this method is reused multiple times, and that it looks like code duplication.

So you will say that the method name is too long anyway. And I would tell you that maybe your class has multiple responsibilities, which is bad as it violates the Single Responsibility Principle (opens new window).

I often say that if you can’t find a decent name for a class or a method, something is probably wrong. It is a rule I use to follow while designing a software by naming things (opens new window).

Don’t abbreviate, period.

It’s often tempting to abbreviate in the names of classes, methods, or variables. Resist the temptation – abbreviations can be confusing, and they tend to hide larger problems.

Think about why you want to abbreviate. Is it because you’re typing the same word over and over again? If that’s the case, perhaps your method is used too heavily and you are missing opportunities to remove duplication. Is it because your method names are getting long? This might be a sign of a misplaced responsibility, or a missing class.

Try to keep class and method names to 1-2 words, and avoid names that duplicate the context. If the class is an Order, the method doesn’t need to be called shipOrder(). Simply name the method ship() so that clients call order.ship() – a simple and clear representation of what’s going on.

Naming things is hard, that’s right, but naming things by their right names is even harder!

My Golden Rule is: if you’re not able to find a name for a class, then ask yourself if this class makes sense, or if you can decouple things a bit more.

7. Keep All Entities Small

No class over 50 lines and no package over 10 files. Well, it depends on you, but I think you could change the number of lines from 50 to 150.

The idea behind this rule is that long files are harder to read, harder to understand, and harder to maintain.

Classes over 50 lines usually do more than one thing, which makes them harder to understand and harder to reuse. 50-line classes have the added benefit of being visible on one screen without scrolling, which makes them easier to grasp quickly.

What’s challenging about creating such small classes is that there are often groups of behaviors that make logical sense together. This is where we need to leverage packages. As your classes become smaller and have fewer responsibilities, and as you limit package size, you’ll start to see that packages represent clusters of related classes that work together to achieve a goal. Packages, like classes, should be cohesive and have a purpose. Keeping those packages small forces them to have a real identity. If the real identity comes out to more than 50 lines, that is ok. This is software engineering; there is no black and white- as Uncle Bob regularly stresses, our craft is about trade-offs.

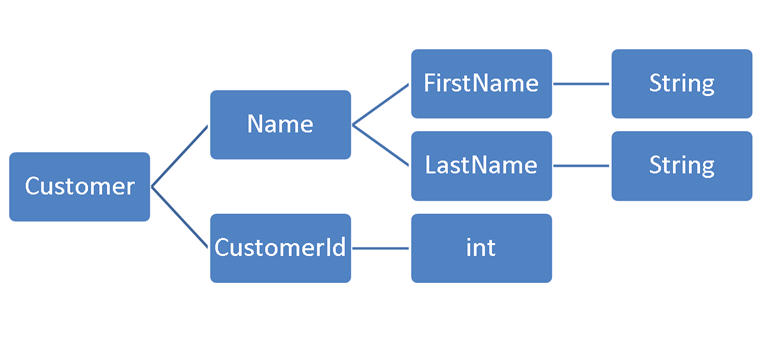

8. Do Not Use Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

I thought people would yell at me while introducing this rule, but it didn’t happen. This rule is probably the hardest one, but it promotes high cohesion, and better encapsulation.

A picture is worth a thousand words, so here is the explanation of this rule in picture.

Source: Object Calisthenics (opens new window)

The main question was Why two attributes? My answer was Why not? Not the best explanation but, in my opinion, the main idea is to distinguish two kinds of classes, those that maintain the state of a single instance variable, and those that coordinate two separate variables. Two is an arbitrary choice that forces you to decouple your classes a lot.

9. Do not Use Getters and Setters

The simplest way to avoid setters is to hand the values to the constructor method when you new up the object. This is also the usual pattern when you want to make an object immutable.

DTOs are appropriate and useful in some situations, especially in transferring data across boundaries (e.g. serializing to JSON to send through a web service); so, they will have getters.

Lets explain in detail why we should avoid getter and setters methods: Lets say we have a class Car1.java

public class Car1 {

public Engine engine;

}

2

3

Now I want to point out that there is not functional difference between a public class with public member and a public class bellow with private member having a getter and setter method.

public class Car2 {

private Engine engine;

public Engine getEngine() {

return engine;

}

public void setEngine(Engine engine) {

this.engine = engine;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

I can read and write engine of car in both classes in almost the same way:

// Car1 member read and write

Car1 car1 = new Car1();

logger.debug("Car1's engine is {}.", car1.engine);

car1.engine = new HemiEngine();

// Car2 member read and write

Car2 car2 = new Car2();

logger.debug("Car2's engine is {}.", car2.getEngine());

car2.setEngine(new HemiEngine();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Point of this example is to show that, I can anything with Car1, I can do with Car2 and vice versa. Whenever we see a public member in a class, very first thought that crosses our mind is "its not safe", but on the other side a getter/setter method a sigh of relief.

Some major disadvantages: Getter/Setter expose implementation level details: Lets save we have api of Car

| Car |

|---------------------------------|

| + getGasAmount(): Liters |

| + setGasAmount(liters: Liters) |

|_________________________________|

2

3

4

5

If you assume that this is a gas-powered car that internally tracks gasoline in liters, then you are going to be right 99.999% of the time. That's really bad and this is why getters and setters expose implementation / violate encapsulation. Now this code is brittle and hard to change. What if we want a hydrogen-fuelled car? We have to throw out this whole Car class now. It would have been better just to have behavior methods like fillUp(Fuel fuel).

Getters and setters can actually be dangerous Using getter method blindly can actually cause problems. Lets say we have debt class and there is a list of debts inside.

public class Debts

{

private List<Debt> debts;

public List<Debt> getDebts()

{

return debts;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Class seems pretty reasonable. I can use this class to get debts and create a report. Simple as that. But, Can I add more debts? There is no setter method. How? Because Java returns reference for collections.

Debts scottsDebts = DebtTracker.lookupDebts(scott);

List<Debt> debts = scottsDebts.getDebts();

// add the debt outside scotts debts, outside the debt tracker even

debts.add(new Debt(new BigDecimal(1000000)));

// prints a new entry with one million dollars

DebtTracker.lookupDebts(scott).printReport();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

One way to guard against this is to return a copy instead. Another way is to have an immutable member. The best way, though, is to not expose the member in any way at all and instead bring the behavior that manipulates the member inside the class. This achieves full isolation of the implementation and creates only one place to change.

Let see how we can avoid getter/setter methods:

Tell, Dont Ask Rule is very simple, classes should not have getter/setter method which simple get/set values, rather there should be method which represent behaviors. Lets explain it with a example. We have BankAccount class which has amount, in below implementation we have setter method with set amount.

public class BankAccount {

private final int amount;

public BankAccount(int amount) {

this.amount = amount;

}

public void setAmount(int amount) {

this.amount = amount;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

This is the code we need to avoid, because it exposes implementation level details. Lets apply the rule and add methods which represent behavior.

public class BankAccount {

private final int amount;

public BankAccount(int amount) {

this.amount = amount;

}

public void depositAmount(int amount) {

this.amount+=amount;

}

public void withdrawAmount(int amount) {

this.amount -= amount;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

This way, implementation level details are hidden and even if you have have to change the way amount is kept in account, your exposed methods will remain the same, providing the same behavior.

There are some places where getter/setter method actually make sense like before updating the state in current object according to some input, we validate the input. The input validation is additional functionality. Purpose of this point to avoid getter/setter methods as much as you can, but if you can think there is no other way, you need to careful while writing your code by keep above points in mind.